A trio of stars just under 5,000 light-years away has definitely broken a long-standing record.

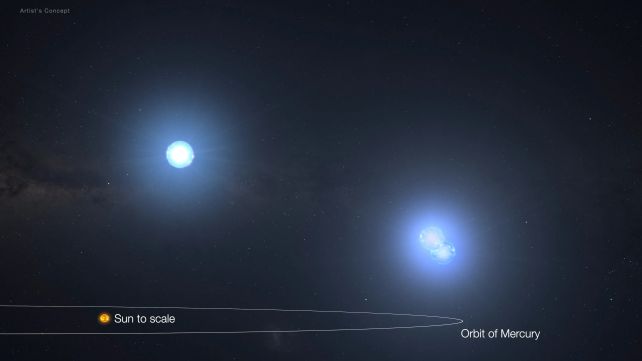

TIC 290061484 is a system of gravitationally bound stars consisting of a tightly orbiting binary pair with a third star orbiting both. Amazingly, they are so close together that the entire system would fit within Mercury’s orbit.

And that’s not all. The close-knit trio seems to have another friend; there is evidence of a fourth star that traces a path at a much greater distance.

All three stars in the central trinity are on a collision course and are destined to collide, merge, become a supernova and leave behind a single neutron star in about 20 million years.

The discovery was made using the TESS exoplanet-hunting space telescope, which is optimized for detecting the smallest changes in a star’s brightness that indicate an orbiting world.

Systems of stars that obscure each other along our line of sight also show changes in brightness, as the stars pass in front of each other, blocking at least some of each other’s light. TESS observations can also detect these brightness changes. This is a powerful tool for finding these systems because, from the distance we see them, they usually look like a single star.

frameborder=0″ allow=accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard writing; encrypted media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

This is the case with the central trinity of TIC 290061484. The orbital plane on which they are all aligned is pretty much to the side of our line of sight, meaning we are treated to different eclipse configurations as the three stars do their work. cosmic dance.

A team of scientists led by astrophysicist Veselin Kostov of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center discovered the system after extensive analysis of TESS data. They used a machine learning algorithm to filter the data based on the expected signal from galaxy eclipses, then released a small army of citizen scientists to further refine the results.

“We are mainly looking for features of compact multi-star systems, unusual pulsating stars in binary systems and strange objects,” says physicist Saul Rappaport of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“It’s exciting to identify a system like this because they are rarely found, but they may be more common than current numbers suggest.”

Once they identified the system as interesting, the researchers could analyze its changes in light to determine its characteristics.

The two stars that make up the central binary clock have masses of 6.85 and 6.11 times the mass of the Sun, with an orbital period of only 1.8 days.

The third star has a mass of 7.9 times the Sun and orbits the central pair in a period of 24.5 days. That period blows the smallest trinity known to date, with an orbital period of 33 days, out of the water.

Finally, the likely fourth star would have a mass of about 6.01 times the mass of the Sun. It is estimated to orbit the central triple circle in a much wider orbit of about 3200 days.

Stars are born from abnormally dense regions of matter within enormous clouds of gas. Normally, such clouds are littered with a number of baby stars, some of which come close enough to merge, while others may spend their entire lives together in orbit.

Most of the stars in the Milky Way Galaxy are in systems like this. If you look up at the night sky, more than half of the stars you see are actually multiple stars, too far away to make out.

We know that multi-star systems exist that we have not yet identified. This discovery suggests there may be many more than we thought. The next step will be to deploy the upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope for the task of finding them once it reaches the sky.

“Before scientists discovered triple-eclipsing triple star systems, we didn’t expect them to exist there,” says astronomer Tamás Borkovits of the Baja Observatory at the University of Szeged in Hungary. “But once we found them, we thought, why not? Roman, too, could reveal never-before-seen categories of systems and objects that will surprise astronomers.”

The research was published in The Astrophysical Journal.