The way the human brain remembers certain individuals is closely related to the way we talk about them.

Neuroscientists have now shown that pronouns like ‘he’, ‘she’ or ‘they’ can activate the same neuron in the brain as a person’s specific name.

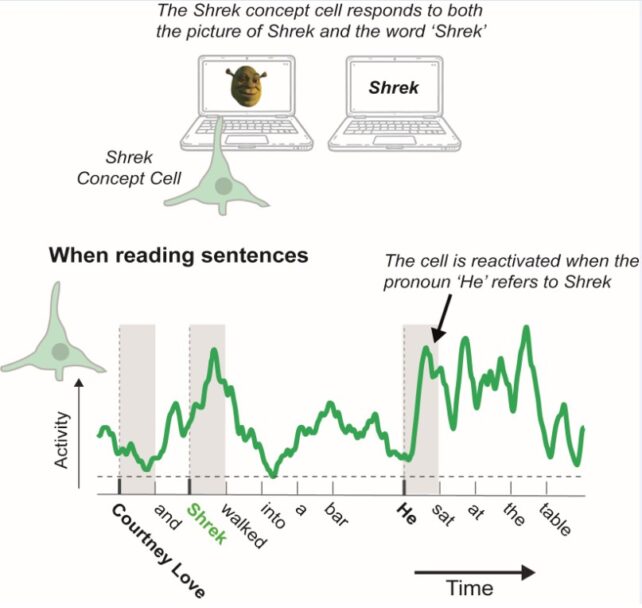

Take these two sentences as an example: “Shrek and Courtney Love walked into a bar. He sat down at a table.” In experiments, the pronoun “he” caused the same neuron in the hippocampus to fire as the word “Shrek.”

The hippocampus supports the retrieval of words, numbers and concepts from our memory, and pronouns appear to be part of that process.

Some neurons in the hippocampus are believed to be ‘concept cells’, although they are more commonly known as Jennifer Aniston cells. In 2005, scientists discovered that photos of celebrities like Jennifer Aniston activated specific neurons in the hippocampus.

In the years since, scientists have substantiated the theoretical existence of these so-called concept cells, which appear to store representations of people, abstract concepts or objects.

Concept cells are activated when a person sees a photo of a specific individual, when he hears or reads that person’s name, or when he tries to recall that person from memory.

Now it appears that they are also reactivated when a pronoun is used as a proxy for a person’s name.

The study is based on brain recordings from patients with intractable epilepsy, who had electrodes implanted deep in their hippocampus to identify where their seizures occurred.

These implants also give scientists the opportunity to study how individual neurons in the hippocampus fire during waking activity.

When a participant was shown a photo of Shrek, researchers noticed that a particular neuron in their hippocampus would fire.

This same neuron was also activated when volunteers were asked to read a passage about Shrek and Courtney Love and the name “Shrek” appeared.

Gradually, that neuron’s activity began to fade, but when the pronoun “he” was used to refer to Shrek in a later sentence, the same “Shrek” neuron activated. In contrast, when volunteers read the pronoun “they”, the same cell did not activate.

In fact, when Shrek was absent in the first sentence, the pronoun ‘he’ did not activate the concept cell ‘Shrek’. This suggests that only pronouns assumed to refer to Shrek activate the concept neuron.

“We had participants answer a question at the end of the sentences about who performed the action,” explains neuroscientist Matthew Self of the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience.

“We were able to predict whether the patients would give the correct answer based on the activity of the individual concept cells.”

Volunteers also read sentences in which two people had the same pronouns. In this case, the person who evoked the most hippocampal activity to begin with was the one who was later assigned the pronoun.

“This could be based on random fluctuations in activity, trial by trial, or on an internal preference for one of the two characters in the sentence,” says Self.

The findings suggest that concept cells help the brain link new information to an already existing concept.

“For example, if we read about Shrek that ‘he’ has put on sunglasses, we can update Shrek’s representation and predict his future appearance,” the study authors write.

Significantly, people who have suffered damage to the hippocampus can sometimes have difficulty producing or understanding pronouns.

“Theories about the developing mental representation of the story during reading suggest that previously read words are stored in working memory so that they can be combined with new information,” the international team explains.

“How brain networks implement such syntactic computations is a topic for future research, which can now be explored.”

The research was published in Science.